Renal replacement lipomatosis (RRL) is a rare end-stage result of the chronic inflammatory/degenerative process. As the renal parenchyma is destroyed due to long-standing insult, it is subsequently replaced by adipose tissue following abnormal fibrofatty proliferation.[1] Even though imaging modality such as ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen is helpful for initial screening, contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) urography is needed to confirm the fibrofatty replacement of renal parenchyma and to assess the renal function. Herein, we present a case of total replacement lipomatosis which was confirmed by CT urography, along with its peri-operative course, histological findings, and post-operative imaging. This case report was written following the CARE guidelines (for Case Reports).[2]

CASE REPORTA 55-year-old lady from a remote part of western Nepal presented to our center with complaints of long-standing occasional abdominal pain localizing in the right loin region, which had increased in intensity over a couple of days. She denied any history of chronic illness or history of seeking medical treatment except for taking over-the-counter analgesics. She admits to knowing that she had a right renal calculus for the past 11 years, but no reports were available. According to the patient, a USG abdomen was done at the time of the first episode of renal colic and was managed conservatively.

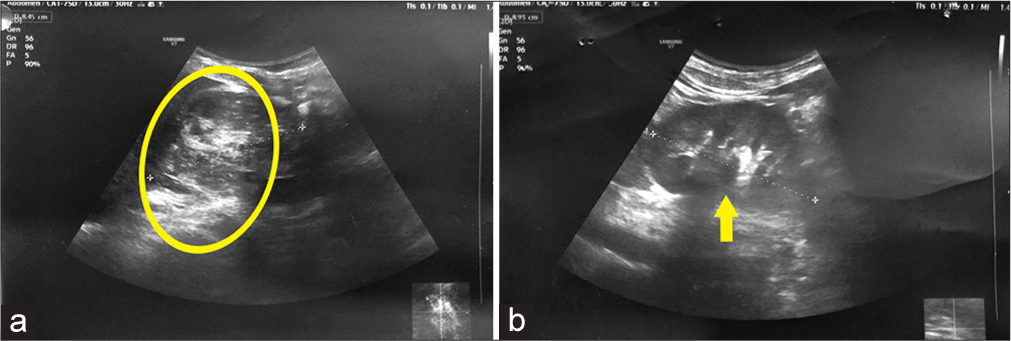

On preliminary examination, she had no significant clinical findings, and routine blood work was unremarkable. USG of the abdomen showed an echogenic enlarged right kidney demonstrating loss of corticomedullary differentiation [Figure 1a and b], with a bright echogenic calculus of approximately 15 × 10 mm size in the renal pelvis resulting in minimal right hydronephrosis.

Export to PPT

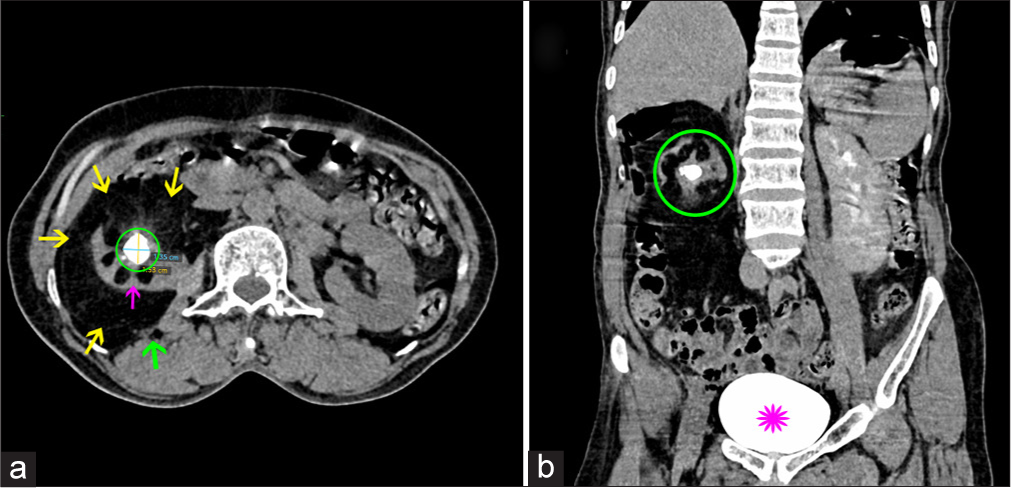

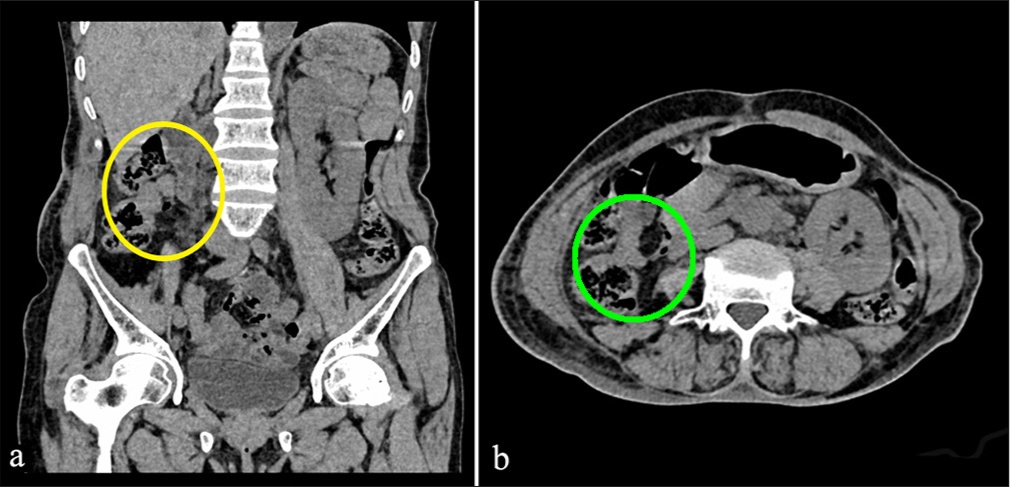

To further investigate the abnormal echogenicity of the right kidney, the patient underwent CT urography [Figure 2a and b]. The urography revealed enlarged right kidney with low attenuation (mean Hounsfield unit [HU] 100 ± 10) of the renal parenchyma suggestive of extensive fatty proliferation in the renal sinus, renal hilum, and perirenal space associated with marked renal parenchymal atrophy and thinning of right renal cortex along with right pyelolithiasis (15.3 × 13.5 × 12.3 mm size, +1255 HU) and mild hydronephrosis. No contrast excretion was seen from the right kidney even after 1-h delayed scan. A note was made of atrophy of the right psoas muscle as well. The diagnosis of right renal replacement lipomatosis (RRL) with non-functioning kidney was made.

Export to PPT

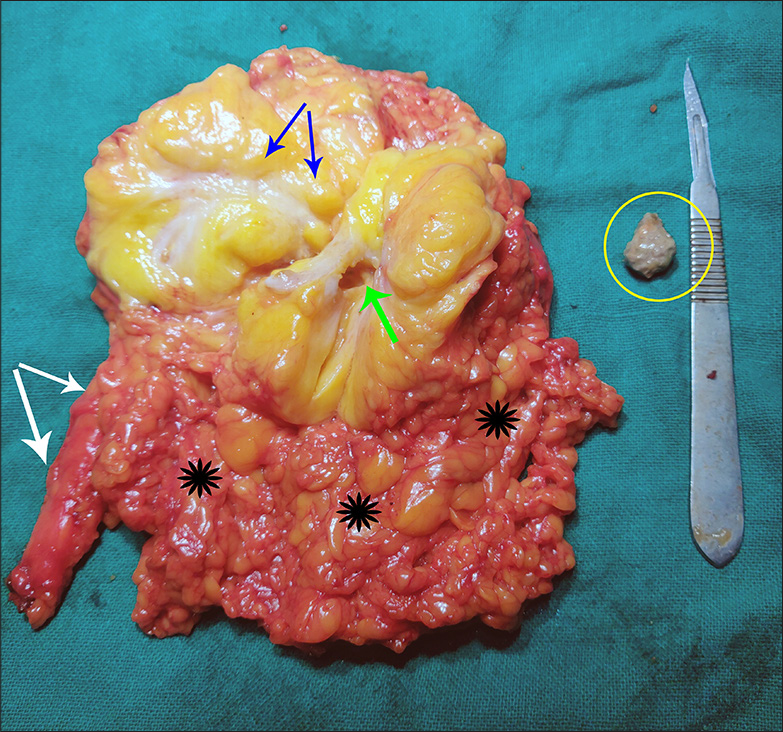

The patient underwent laparoscopic right radical nephrectomy, in which the right kidney up to mid-ureter along with peri-nephric fat and Gerota was excised in toto [Figure 3]. Intraoperatively, dense adhesion was found between the Gerota’s fascia with psoas muscle posteriorly and the peritoneum with duodenum medially. The perinephric fat was toxic-looking. Post-operative recovery was uneventful except for prolonged ileus for 3 days, and the patient was discharged on the 4th post-operative day.

Export to PPT

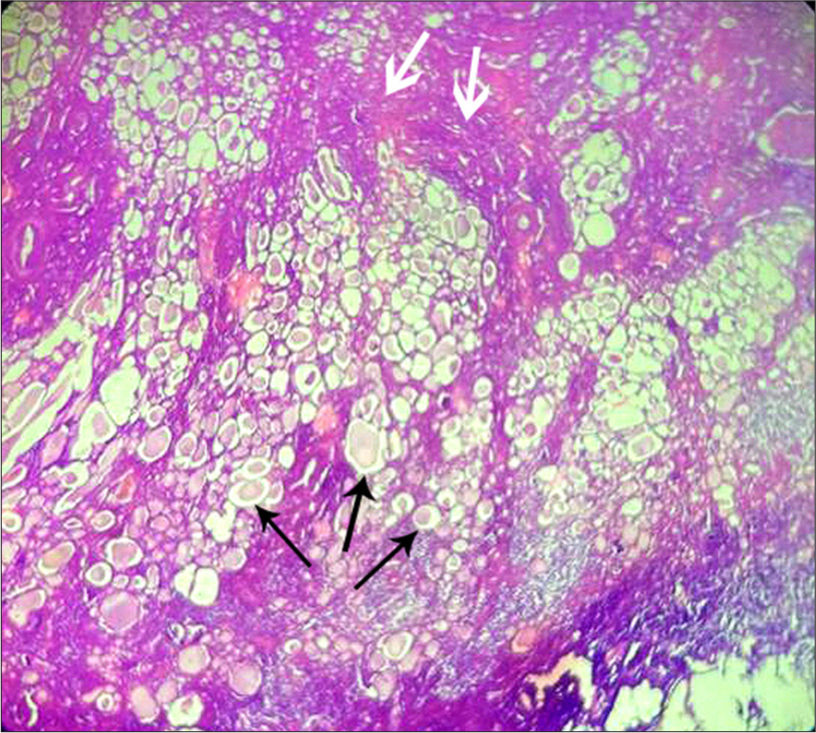

Histopathology of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of RRL of the kidney with abundant adipose tissue having sparse fibrous islands of marked inflammation suggestive of chronic pyelonephritis [Figure 4]. Few of these islands contained dense chronic interstitial inflammatory infiltrates, dilated tubules lined by cuboidal to flattened epithelium, and filled with casts.

Export to PPT

At 3-month follow-up, she was symptom-free and doing well with normal renal function. Plain CT abdomen showed no residual disease [Figure 5a and b], and the patient was finally discharged from care.

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONInitial reports of RRL date back to 1931 by Kutzmann as mentioned by Peacock and Balle in their paper from 1936.[3] The exact pathogenesis remains unknown, but it is thought to result from chronic inflammation and is not limited to the kidney. More than 75% of cases are associated with lithiasis,[4] as observed in our case. Other associations include aging, obesity, atherosclerosis, steroid use, renal tuberculosis, renal infarction, and renal transplant.[5,6]

This entity is clinically significant for both radiologists and urologists, as it mimics a renal tumor and has other important differential diagnoses such as malakoplakia, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP), renal tuberculosis, lipoma, liposarcoma, and angiomyolipoma.[7,8] While XGP can also occur in the natural history of a chronically obstructed kidney, both benign conditions differ histologically. In XGP, lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) infiltrate the renal parenchyma, while in RRL, the fat cells remain outside the atrophying renal parenchyma.[5]

RRL lacks specific clinical findings or signs, with diagnosis relying solely on imaging, subsequently confirmed by histology. Our patient did not exhibit severe symptoms throughout, which may explain the delay in seeking treatment. USG is the first modality of imaging done at presentation. The presence of echogenic central sinus in the affected kidney raises the suspicion of RRL and leads to further evaluation by CT.[9] CT urography is considered the optimal imaging technique to both diagnose and rule out other possibilities. Magnetic resonance imaging is typically performed only when CT contrast is contraindicated. The severity or extent of lipomatous replacement correlates with the delay in presentation. A dimercaptosuccinic acid scan can be conducted if there are doubts regarding kidney function.[10]

The treatment of choice is simple nephrectomy with complete removal of the involved fatty tissue.[11] A minimally invasive technique should always take precedence if feasible and resources allow.

CONCLUSIONRRL is a rare but clinically important entity occurring due to long-standing chronic inflammation. Even though it is a benign condition, it can lead to significant morbidity. CTurography is the best imaging modality that helps diagnose and differentiate it from other grave conditions such as XGP and renal cell carcinoma.

Comments (0)